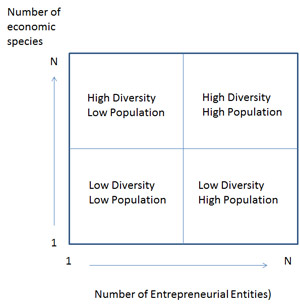

All of these are spontaneous self-starting processes. When we look at “evolution” we know to look at the many types of species and their evolutionary relationships, in today’s view, genetic phylogeny. When we look at “ecosystems” we know to look at the patterns of species diversity and distribution. So they are not the same viewpoint, but they are made up of the same things. When we look at economies, I am willing to bet most people do not separate the two major aspects of the economies — the range or diversity of types of economies and their evolutionary relationships derived over very long periods of time and in addition the patterns of economic species diversity and distribution in a region.

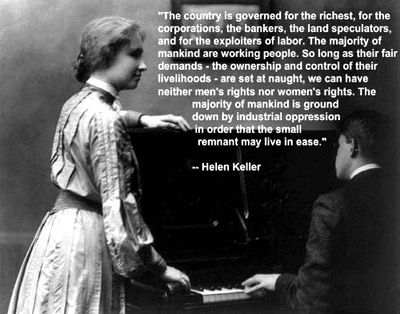

Natural evolution has no ultimate goal, no defined milestones, no direction, and no purpose. The results of evolution are on-going rudderless experiments. Each element in the experiment has only two major objectives, survive and reproduce. Organisms respond to the entire range of conditions that make up their environment. Natural selection is a blind tool choosing those genes that allow individuals to survive and reproduce best. Only one species would exist were it not for naturally occurring variation. Diverse conditions lead to diverse species. While there is no natural management of evolution, there are well-known examples of artificially managed evolution. Continue reading